|

SE735 - Data and Document Representation

& Processing |

|

Lecture 6 - How Models and Patterns Evolve & When Models

Don’t Match |

Chapter

5: How Models and Patterns Evolve

The

Big Ideas of Chapter 5 (and of the Information-Powered Economy)

·

Business architectures co-evolve with

technology

·

Information technology has radically changed

the structure of firms

·

Information about goods becomes a good (or a

service?)

·

Business models are shifting from

forecast/schedule-driven to demand/event-driven

·

Business relationships/architectures shifting

from tightly to loosely coupled

·

Business models are shifting from proprietary

to standard models with reusable components

Co-evolution

of Business Models and Enabling Technologies

·

Business patterns are continuously evolving,

mostly as a result of changes in information and communications technology

·

Businesses don't just select a pattern and

follow it; they may have to adapt a pattern or change to a different pattern to

succeed

·

New technologies pose predictable problems

for the business models of incumbents (as opposed to new firms) in an industry

"The Nature of the Firm" – Coase

(1937)

·

Why do firms exist at all? Why does an

entrepreneur hire people instead of "renting" them in the

marketplace?

·

A transaction costs analysis says that firms

are created when hierarchical coordination of internal processes is more

efficient than carrying out the same processes externally "in the

market"

·

The marketplace sets prices and coordinates

the actions of self-interested buyers and sellers through the "invisible

hand" (Adam Smith), but it also imposes "transaction costs"

·

When transactions are brought inside, the

administrative coordination with the "visible hand" of management and

authority can reduce transaction costs

"Transaction Costs"

·

SEARCH – Discovery of potential business

partners

·

INFORMATION ANALYSIS – Determining what

products and services are offered and whether the partner is appropriate on

other dimensions

·

BARGAINING – Proposing the terms of a

business relationship

·

DECISIONMAKING – Agreeing on the terms and

ensuring their fit with other business processes

·

MONITORING – Ensuring that the terms and

conditions are being met

·

ENFORCEMENT – Taking corrective action if

they are not

"The New Industrial State"

The size of General Motors is in the service not

of monopoly or the economies of scale but planning…and (thanks to) this

planning—control

of

supply, control of demands, provision of capital, minimization of risk—there is

no clear limit to the desirable size (of the company.)

Size is the general servant of technology,

not the special servant of profits. Small businesses have no need for

technological innovations and

can

hardly afford to keep up with new technologies (as big businesses do) and

therefore struggle to survive in the economical whirlwind of

production and

profit. The enemy is advanced technology, the specialization and organization

of men and process that this requires and

the

resulting commitment of time and capital.

John Kenneth Galbraith (1957)

The Hierarchical Firm

·

The traditional industrial corporation of the

mid-to-late 20th century was large, vertically integrated, and hierarchically

organized to produce standardized products for mass markets

·

In 1960 all but two of the world’s largest

companies based in US General Motors earned as much in profits as 10 biggest

firms from France, UK, Germany combined (30 total)

·

US firms produced 50% of world output; this

amounted to more than the next 9 industrial nations combined

Example: Ford's River Rouge Plant

·

The ultimate in vertical integration - with

docks on the Rouge River, 100 miles of interior railroad track, its own

electricity plant, and ore processing, raw materials were turned into running

vehicles within this single complex

·

1.5 miles (2.4 km) wide by 1 mile (1.6 km) long,

including 93 buildings with nearly 16 million square feet (1.5 km²) of factory

floor space

·

Over 100,000 workers worked in this single

complex in the mid 1900's

Transaction Costs and New Technologies

·

New technologies (e.g. telephone, mainframe

computer) reduce coordination costs so firms can get bigger...

·

But what if new technologies reduce the

external costs proportionally more than internal costs?

·

As communication, coordination, and

monitoring costs decline because of new technology and more organizational

autonomy it becomes possible to outsource non-essential functions

·

And makes it cheaper to work with new

business partners on shorter term, more ad hoc relationships

·

Technical standards for product description

and document exchange can also be seen as technology that reduces transaction

costs

From

Hierarchy to Network

·

Today, the large vertical integrated firm of

the mid- to late- 900s has been transformed into a more "network"

form, no longer driven by command-and-control

·

IBM, Cisco and other large firms are

repositioning themselves as comprehensive "service networks" whose

business units are both more autonomous and collaborative

·

Competition is increasingly between entire

supply chains or ecosystems, not just between firms

·

This requires large amounts of formal and

informal information exchange

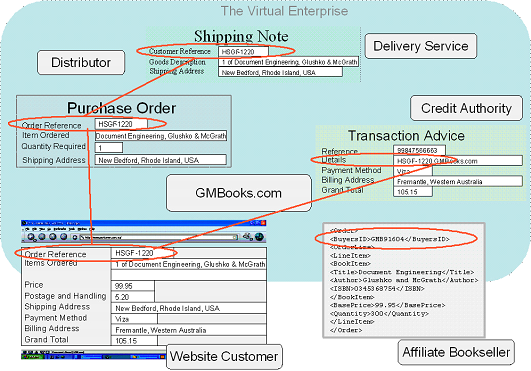

5.3 Information About Goods Becomes a Good 7

Information

About Goods Becomes a Good

·

Information about the supply chain is taking

on independent value

·

Information about where products are, who

uses them, and when and how they are used can be worth more than the products

themselves

·

Once inventory and

information are equivalent, the boundary between the physical and virtual

worlds becomes blurred

·

New services are

arising from the aggregation of information about business transactions

Example: UPS Supply Chain Solutions

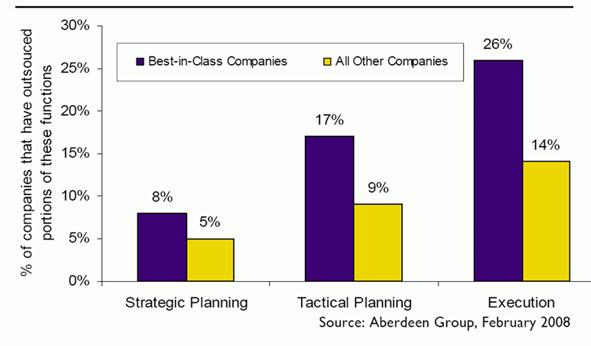

Smart Firms Outsource Their Logistics

5.4 New Business Models

for Information Goods 9

Toward

On Demand/Event-Driven Business Models

·

No forecast can ever be as accurate as actual

sales and demand information

·

The key to supply chain optimization isn't

moving things faster according to plans, it is moving things smarter according

to actual demand

·

"Information-driven decisions" can

be make more reliably and with less latency when sensor networks collect

information

·

The Internet has vastly increased the

viability of direct sales for information goods

·

Two especially significant patterns are

evolving for the creation and distribution of information goods and software:

o

the

open access movement in scholarly and scientific publishing that seeks lawful

free access to online publications

o

the

trend toward software as a service (SaaS).

From Forecast- or Schedule-Driven to

Demand- or Event-Driven Models

Example: GPS & Sensor-Driven "Precision

Agriculture" [1]

Example: GPS & Sensor-Driven "Precision

Agriculture" [2]

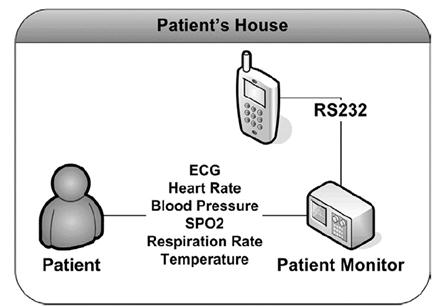

Example: Mobile Telemedicine for Home Care and Patient

Monitoring

Example: Mobile Telemedicine – Patient Monitor

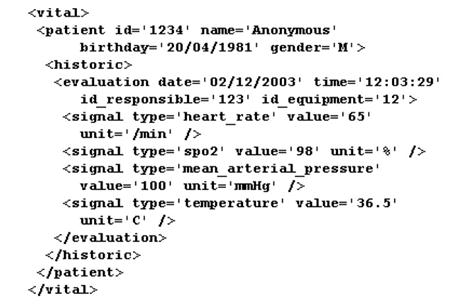

EDF+

Data Format

·

1990 - European Data Format (EDF) - simple and flexible format for

exchange and storage of multichannel biological and physical signals

·

2003 - EDF+ extension of EDF that can also contain interrupted

recordings, annotations, stimuli and events.

From Tightly Coupled to Loosely Coupled Models

More flexible business

models require the loosely coupled architecture of the Internet

Tight

Coupling

·

"Tight coupling" between two

businesses, applications or services means that their interactions and

information exchanges are completely automated and optimized in

performance...

·

... by taking advantage of knowledge of their

internal processes, information structures, technologies or other private

characteristics that are not revealed in their public interfaces

·

... and usually implemented with a custom

program that fit only between the two of them

·

Tight coupling is most often used, and

usually limited to, situations in which the same party controls both ends of

the information exchange

The

Integration Challenge

·

Can we have integration and loose coupling at

the same time?

·

The idea of service-oriented integration says

we can

·

But we can get there from here?

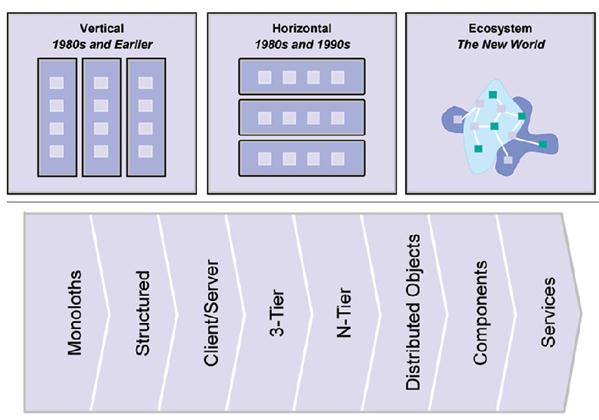

Co-Evolution

of Business and Technology Architecture

Document-

or Service-Oriented Integration

·

Loose coupling—in particular using XML documents to define interfaces—allows

for the transparent scalability of business process automation as browser-based

tasks are incrementally upgraded to computer-mediated ones

·

Internet protocols and XML are enabling

"loosely coupled" architectures and "coarse-grained"

information exchanges that make far fewer (or no) assumptions about the

implementation on the "other side"

·

When integration is done with loose coupling,

the two sides can make (some) changes to their implementations without

affecting the other

·

This is even more true when they communicate

through an "integration hub" which can further abstract their

implementation by doing transport protocol/envelope/syntax translation for them

·

The particular integration technology for

loose coupling is less important than the philosophy or business model that

requires it – treating different organizations, applications, and devices as

loosely-coupled cooperating entities regardless of where they fit within or

across enterprise boundaries

Service

Oriented Architecture – A Conceptual Perspective and Design Philosophy

·

Business processes are increasingly global

and involve widely dispersed parts of an enterprise or multiple enterprises

·

A business needs to be able to quickly and

cost-effectively change how it does business and who it does business with

(suppliers, business partners, customers)

·

A business also needs more flexible

relationships with its partners and "assets" to handle variable

demands

Web

Services {and,vs} Service

Oriented Architecture

·

Web services are an important PHYSICAL

architectural idea and a set of standards and techniques for loose coupling

·

Service Oriented Architecture is a CONCEPTUAL

architectural perspective and design philosophy for loose coupling

·

MBAs and CIOs talk about SOAs, software architects

and developers talk about web services

Web

Services

·

Web Services -- with a capital "S"

-- generally means a particular set of specifications for doing

service-oriented integration with XML documents as the "payload" that

conveys the information required by the service interface

·

(Or put another way -- the interface is

specified using an XML schema that defines in a formal way the information the

service expects and how it should be structured)

·

The most important Web Service specifications

are those for a service's public interfaces (Web Service Description Language)

and for the messaging protocol used to send and receive XML documents through

those interfaces (SOAP)

The

Service Discovery Myth

·

Many discussions about services highlight the

concept of service discovery and a specification called UDDI (Universal

Description, Discovery and Integration)

·

UDDI was proposed as a kind of services

"white" and "yellow" pages directory that would enable

services to be registered by their providers and discovered by potential users,

all by automated means

·

But UDDI is mostly used for

"internal" service directories and rarely for "public" ones

·

Most service relationships are established

"offline" and then the information about how to access the service is

built into the service requestor's implementation

WS-*

("star" or "splat")

·

The major platform and enterprise software

vendors have developed and "standardized" a few dozen specifications

for extending the basic

·

Web Services specifications to handle issues

that emerge in complex distributed applications and service systems

·

These specifications cover things like

security, multi-hop addressing, process choreography, policy assertion,

performance management, ...

·

Their proponents argue that these additional

specifications are essential for service oriented computing to be viable for

enterprise-level applications and services

·

But they've made Web Services (with a capital

"S") seem needlessly complex for a great many applications where they

might have been useful Many services are being implemented today with simpler

protocols

Web-based

Services

·

This is a category coined by Erik Wilde for

his courses at the I-school to mean "Web Services and any services that

use any Internet protocol"

·

This includes services implemented using the

basic HTTP protocol and its mechanisms for providing "better service"

using content negotiation (provide different information to the client based on

the type of browser, etc.)

·

This broader category makes it easier to

understand and make tradeoffs in the design and implementation of services

Chapter 6: When Models Don’t Match

Four Ways to Misunderstand a Document Component

Differences in Content:

· option a. <A>USD 100</A>

·

option b. <A>One

Hundred US Dollars</A>

·

option c. <A>$US100</A>

Differences in Encoding:

·

option a. <Amount>USD

100</Amount>

·

option b. USD,100

·

option c. CUR:USD|AMT:100

Differences in Structure:

· option a. <Amount>USD 100</Amount>

· option b. <Currency>USD</Currency><Amount>100</Amount>

· option c. <Amount>100<Currency>USD</Currency></Amount>

Differences in Semantics:

· option a. <Amount>USD 100</Amount>

· option b. <PreTaxAmount>USD90</PreTaxAmount><Tax>USD10</Tax>

· option c. <Price>USD 100</Price>

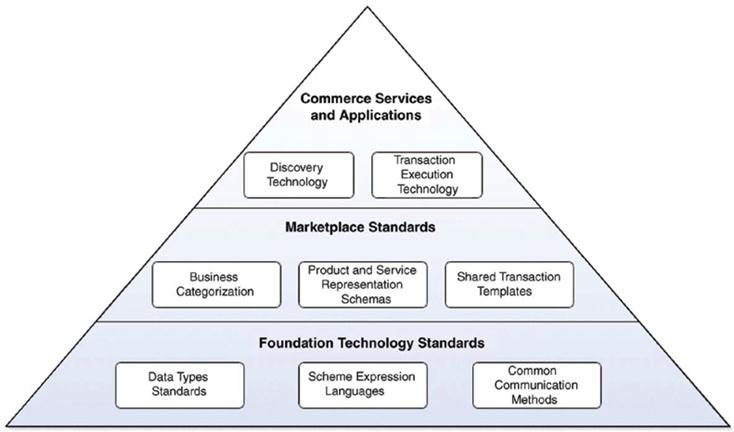

The Interoperability Challenge

The

Interoperability Problem

·

The vocabulary problem implies an interoperability

problem

·

This means that two applications or services

can't use each other's models or document instances "as is"

·

Some interoperability problems can be

detected and resolved by completely automated mechanisms

·

Other problems can be detected and resolved

with some human intervention

·

Other problems can be detected but not

resolved

·

Some problems can go undetected

Syntactic

and Semantic Interoperability

·

Syntactic interoperability is just the

ability to exchange information. It requires agreement or compatibility at the

transport and application layers of the communications protocol stack, with the

messaging protocol and format, and with messaging choreography / sequencing

·

Syntactic interoperability is necessary but not

sufficient

·

Semantic interoperability requires that the

content of the message be understood by the recipient application or process

The

E-Business "Standards Pyramid"

Why

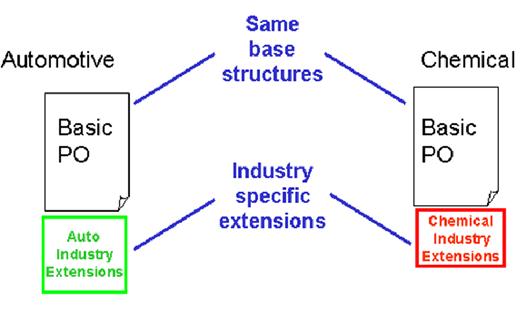

Semantic Interoperability Problems Are Often Inevitable

·

Each new vocabulary for a particular industry

is a step forward for that community, but proliferates definitions of

information models that are

·

common to many of them Since the distinctive

or specialized parts of each vocabulary are the industry-specific

"vertical" parts, a lot of attention gets paid to them

·

In contrast, relatively less effort is given

to the "horizontal" parts that seem more familiar or understandable

·

Nevertheless, any large company – even highly

verticalized ones – engages in diverse business

activities that require it to understand multiple vocabularies at different

times

Vertical

and Horizontal Vocabularies Must Work Together

When

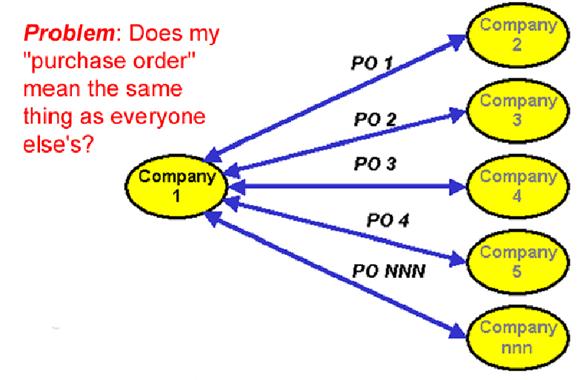

Models Don't Match

·

Suppose you publish your web service

interface description and tell the world "my ordering service requires a

purchase order that conforms to this schema"

·

This says "send me MY purchase

order" not "send me YOUR purchase order"

·

How likely is it that the purchase orders

being used by other firms will be able to meet your interface requirement,

either directly or after being transformed?

How

Bad Can the Interoperability Problem Be?

The Interoperability Target

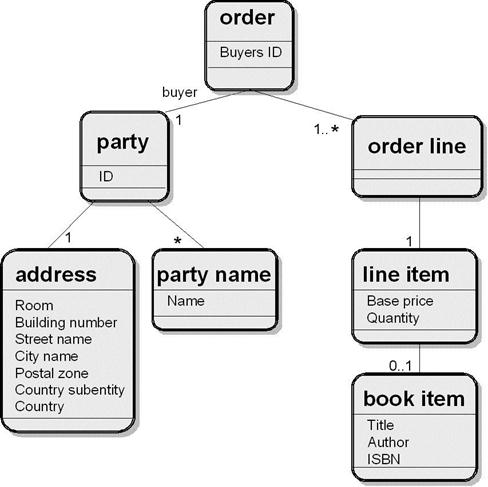

Conceptual Model for Electronic Orders

Physical Model (XML Schema) for Electronic Orders

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name=“PartyNameType”>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name=“Name” type=“xs:string” minOccurs=“0”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name=“AddressType”>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name=“Room” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“BuildingNumber” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“StreetName” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“CityName” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“PostalZone” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“CountrySubentity” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“Country” type=“xs:string”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name=“OrderLineType”>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name=“LineItem” type=“LineItemType”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name=“LineItemType”>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name=“BookItem” type=“BookItemType”/>

<xs:element name=“BasePrice” type=“xs:decimal”/>

<xs:element name=“Quantity” type=“xs:int”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name=“BookItemType”>

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name=“Title” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“Author” type=“xs:string”/>

<xs:element name=“ISBN” type=“xs:string”/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

</xs:schema>

The XSD Schema for the

Expected Order [1]

<xs:schema xmlns:xs="http://www.w3.org/2001/XMLSchema"

elementFormDefault="qualified">

<xs:element name="Order" type="OrderType"/>

<xs:complexType name="OrderType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="BuyersID"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="BuyerParty"

type="PartyType"/>

<xs:element name="OrderLine"

type="OrderLineType"

maxOccurs="unbounded"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name="PartyType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="ID" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="PartyName"

type="PartyNameType"/>

<xs:element name="Address" type="AddressType"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name="PartyNameType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="Name" type="xs:string" minOccurs="0"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

*

The XSD Schema for the

Expected Order [2]

<xs:complexType name="AddressType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="Room" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="BuildingNumber"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="StreetName"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="CityName"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="PostalZone"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="CountrySubentity"

type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="Country" type="xs:string"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name="OrderLineType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="LineItem"

type="LineItemType"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name="LineItemType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="BookItem"

type="BookItemType"/>

<xs:element

name="BasePrice" type="xs:decimal"/>

<xs:element name="Quantity" type="xs:int"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

<xs:complexType name="BookItemType">

<xs:sequence>

<xs:element name="Title" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="Author" type="xs:string"/>

<xs:element name="ISBN" type="xs:string"/>

</xs:sequence>

</xs:complexType>

Instance

of an Electronic Order that conforms to this schema

<?xml

version=“1.0” encoding=“UTF-8”?>

<Order>

<BuyersID>GMB91604</BuyersID>

<BuyerParty>

<ID>KEEN</ID>

<PartyName>

<Name>Maynard

James Keenan</Name>

</PartyName>

<Address>

<Room>505</Room>

<BuildingNumber>11271</BuildingNumber>

<StreetName>Ventura Blvd.</StreetName>

<CityName>Studio City</CityName>

<PostalZone>91604</PostalZone>

<CountrySubentity>California</CountrySubentity>

<Country>USA</Country>

</Address>

</BuyerParty>

<OrderLine>

<LineItem>

<BookItem>

<Title>Document

Engineering</Title>

<Author>Glushko and McGrath</Author>

<ISBN>0262072610</ISBN>

</BookItem>

<BasePrice>99.95</BasePrice>

<Quantity>300</Quantity>

</LineItem>

</OrderLine>

</Order>

Recognizing Equivalence

Variations in strategies,

technology platforms, legacy applications, business processes, and terminology

make it difficult to use compatible documents

Content Conflicts

·

Content conflicts

occur when two parties use different sets of values for the same components

·

e.g. Order Fragment with Base Price Content Conflict

<LineItem>

<BookItem>

<Title>Document

Engineering</Title>

<Author>Glushko and McGrath</Author>

<ISBN>0262072610</ISBN>

</BookItem>

<BasePrice>$99.95</BasePrice>

<Quantity>300</Quantity>

</LineItem>

·

The base price for the

book contains a $ symbol.

·

This creates a data

type conflict in the content of the component.

·

GMBooks.com has

defined BasePrice in its XML schema as a decimal

(meaning a positive or negative number with a decimal point) and this does not

specify a currency code or symbol

·

The $ symbol in the

base price value sent by the affiliate may cause it to be rejected by the

GMBooks.com order system

Encoding Conflicts

A

more obvious way in which information exchanges can conflict is at the level of

encoding—that is, the syntax chosen for implementing the exchange or the way

information is represented within that syntax.

Syntax Conflicts

·

The most apparent

differences in encoding occur when two different syntaxes are chosen

e.g. [1] Order Encoded in UN/EDIFACT (ISO

9735) standard Syntax

UNH+0GMB91604004600001+ORDERS:1:911:UN+362910

04061815???:15’

BGM+120+362910+9’

DTM+4:040618:101’

NAD+BY+KEEN::91++MAYNARD JAMES KEENAN’

NAD+VN+GMBOOKS.COM::92++GM BOOKS LTD’

UNS+D’

LIN+1’

PIA+1+0262072610:IS’

IMD+F+2+:::DOCUMENT ENGINEERING BY

GLUSHKO AND MCGRATH’

QTY+21:300.0000:EA’

PRI+CON:99.95’

UNS+S’

CNT+2:2’

UNT+23+000091604004600001’

·

It is not

immediately compatible with the order example in XML.

·

But as UN/EDIFACT

is the only internationally recognized standard for electronic order documents

·

The affiliate might

be annoyed to be told by GMBooks.com that it is using an unacceptable format.

e.g. [2] Order Encoded in ANSI ASC X12 Syntax

ST*850*000820

BEG*00*SA*820**040605

N1*ST*KEEN*92*GMB91604

PO1*1*1*EA***EN*0262072610

PID*F****Document Engineering GLUSHKO MCGRATH

PO4**300*EA

CTT*2

SE*56*000820

·

Popular EDI syntax

developed by the American National Standards Institute known as ANSI ASC X12.

·

During the 1990s this

syntax was increasingly adopted by U.S. publishers and booksellers and built

into their order processing systems

Issues

·

The components of these

examples require mapping or transforming into their GMBooks.com counterpart.

·

A one-to-one mapping

of document components is not always achievable

·

Numerous mapping or

translation tools exist to convert EDI and other formats to XML (and vice

versa), but most of them work near the surface of the message to relate parts

of one message to the other and don’t provide much support for understanding or

reusing the models below the surface

Grammatical Conflicts

·

Many XML encoding

conflicts result from different uses of the element and attribute constructs

·

Encoding conflicts

can be resolved if the underlying semantics and structures are compatible

o If two parties have been creating models for the same

business context, they will have similar conceptual models and assemblies of

structures, any different choices at the encoding phase should be easy to

diagnose and reconcile.

Structural Conflicts

·

Conflicts arise

when the models of documents or their components have different structures.

·

Even when both

parties use the same encoding rules, structural conflicts can cause

interoperability problems.

Component Assembly Conflicts

·

Two parties assemble

components into structures in incompatible ways.

·

This may happen

when they view some of the components in a different context.

o Even both parties have the same models for names,

addresses, and other components in isolation, the differences in how they are

put together results in different hierarchies and different documents

·

More significantly,

the position of components in the hierarchy affects their meaning

·

The earlier in the

modeling process that two parties make different decisions, the greater the

possibilities for their models to be incompatible

Component Granularity Conflicts

·

Conflicts that

derive from identifying components in different levels of details—these are

issues about the granularity of

structure in a component.

·

e.g. under

specified vs over specified granularity

|

A.

BuyerParty Fragment with

Underspecified Granularity |

B.

BuyerParty Fragment with Overspecified Granularity |

|

<BuyerParty> <ID>KEEN</ID> <PartyName> <Name>Maynard

James Keenan</Name> </PartyName> <Address> <StreetAddress>11271 Ventura Blvd. #505</StreetAddress> <City>Studio

City 91604</City> <CountrySubentity>California</CountrySubentity> <Country>USA</Country> </Address> </BuyerParty> |

<BuyerParty> <ID>KEEN</ID> <PartyName> <FamilyName>Keenan</FamilyName> <MiddleName>James</MiddleName> <FirstName>Maynard</FirstName> </PartyName> <Address> <Room>505</Room> <BuildingNumber>11271</BuildingNumber> <StreetName>Ventura Blvd.</StreetName> <CityName>Studio City</CityName> <PostalZone>91604</PostalZone> <CountrySubentity>California</CountrySubentity> <Country>USA</Country> </Address> </BuyerParty> |

·

These granularity

differences result in one-way interoperability—a more granular model can be

transformed into a less granular model, but not vice versa.

Semantic Conflicts

·

The most complex

issues affecting interoperability in document exchange are the result of

semantic conflicts.

·

Even if we resolve

the encoding and structural conflicts, we have a long way to go to ensure

meaningful communication of information

Vocabulary Conflicts

·

Two modelers will

often choose different names for the same component

·

Two possible

solutions:

o controlled vocabularies, a closed set of defining terms

o ontologies, which define the meaning of terms using a formal or

logic-based language.

Scoping Conflicts

·

Different document

samples can lead to incompatible models

·

The decision about

what information sources to analyze when developing a model—the inventory and

sampling phase—occurs early in the modeling process.

·

If two parties

begin with different samples, their models can diverge at a very early stage

and chances are that the resulting models will be incompatible

·

The inventory will

include information sources that are not in the form of traditional documents, such

as databases, spreadsheets, web pages, and the people who create and use them