|

SE735 - Data and Document Representation &

Processing |

|

Lecture

9 - Designing Business Processes with Patterns |

Why We Use Patterns

Simplify work.

Encourage best practices

Assist in analysis.

Expose inefficiencies.

Remove redundancies.

Consolidate interfaces.

Encourage modularity and transparent substitution.

How We Use Patterns

· Adopt pattern (it

already fits what I do)

·

Adapt to pattern (change what I do to fit pattern)

·

Adapt pattern (change the pattern to fit what I do)

·

Invent new pattern (no pattern fits)

·

Instantiate the adopted/adapted/new pattern

Patterns in Document Engineering

·

The essence of Document Engineering is its

systematic approach for discovering and exploiting the relationships between

patterns of different types

·

Working from the top down to connecting a business

model to the document/process and information component level can ensure that a

business model is feasible

·

Working from the bottom up to establish a business

model context on transactions and information exchanges can ensure that we are designing

and optimizing the activities that add the most value

·

These relationships between patterns "bridge

the gap between strategy and implementation"

Patterns in

the "Model Matrix

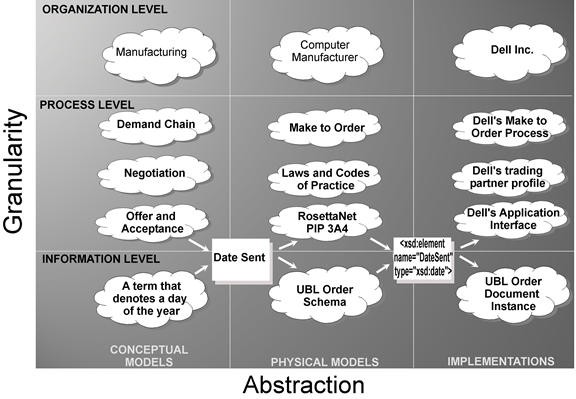

Read the Model Matrix Left-to-Right as:

General Pattern => Specialized Pattern

=> Adapted Pattern

The

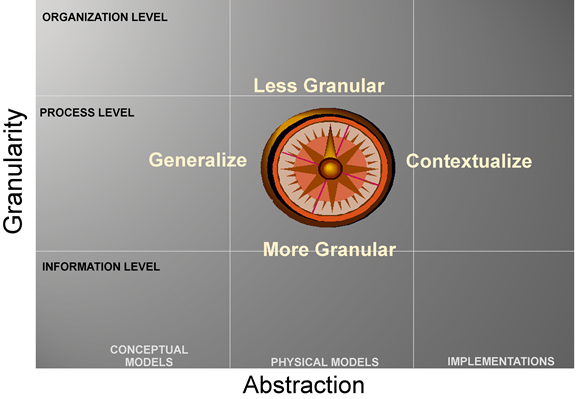

"Pattern Compass"

Movement from left-to-right is in the Contextualize

direction - making patterns more specific (or specialized) for a particular

context.

Movement in the reverse direction from right-to-left

follows the Generalize direction to select patterns that are more abstract.

Movement from top-to-bottom on the Granularity

dimension increases the granularity of the pattern.

Movement in the reverse direction from bottom-to-top

on the Granularity dimension reduces the granularity of the pattern. We

progressively hide the lower level details to create a coarser, big picture

view of the pattern; now we're looking at the forest instead of the trees.

Contextualizing Patterns

·

If you are

in a context where there are no existing processes or solutions, you will

probably identify goal-oriented processes and more general constraints

·

Your

challenge will be to contextualize these general or abstract processes by

identifying and applying the constraints in your target context(s)

·

You have a

strategic opportunity to analyze a range of potentially appropriate process

patterns and select the one(s) that best satisfy the abstract goals of your

business model

Contextualization and Innovation

·

So

Contextualization == Innovation because you will have to make choices about how

to frame the context and satisfy abstract constraints with specific instances

·

The pattern

you choose will reinforce the context by emphasizing some requirements and

rules more than others

·

One pattern

may better describe the As-IS model, but another might provide more insight,

and a better roadmap, for getting to a TO-Be model

Generalizing Patterns

·

In

contrast, if you are evaluating or re-engineering existing processes or

solutions, you will probably identify transactional processes and specific

constraints on information components created or consumed by the processes

·

To

generalize is to take a more abstract view of something by eliminating

requirements or constraints, creating a less contextualized perspective

·

If

generalize = de-contextualize, then we can generalize by "unapplying" the "context dimensions" from

Chapter 8 and assessing whether we can ignore the requirements they had imposed

Generalizing Business Model Patterns

·

You can

identify business model patterns inductively, by looking at specific examples

of businesses and factoring out repeating elements to identify the pattern:

·

Bank in

supermarket

·

Fast food

franchise in supermarket

·

Post office

in supermarket

==> Complementary product or service for

supermarket customers "plugged into" supermarket

==> Complementary product or service for

customers of business type X plugged into type X establishment

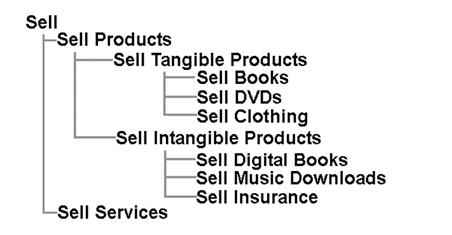

e.g. Generalization in a Process Pattern Repository

Varying the

Granularity of Patterns

The granularity of an As-Is process model is shaped by

the sources of information about processes and whether the analysis was more

top-down or bottom-up.

Coarser grained models suggest patterns that encourage

new specializations.

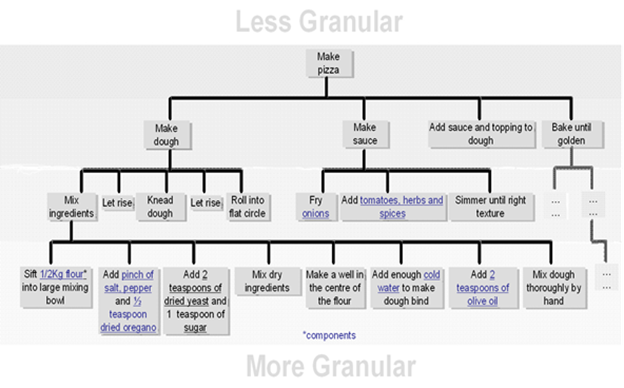

Example: (Cooking) Recipe Patterns

·

A recipe

describes both objects and structures (ingredients) and the processes (cooking

instructions) for creating a food dish

·

Recipes are

typically written with narrow scope to describe how to make specific dishes

Pizza Patterns

Using Pizza Patterns

·

What

granularity of a pizza recipe is best for teaching new employees at a pizza

franchise?

·

What

granularity is best for differentiating pizza varieties and recognizing

possibilities for new ones?

·

What

granularity is most likely to reveal that making pizza and making bread have

something in common, yielding the hybrid model of focaccia?

Following Recipes Exactly: Implementations as

Patterns

·

Sometimes

we want to replicate a process exactly as it has been implemented somewhere

else

·

This means

we want to apply a physical model rather than a conceptual one and will use the

same implementation technology and the specific values that fill the roles and

activities in the source process

·

When would

we want to do this?

·

What are

the costs and benefits of using implementations as patterns?

"Process Rituals" and "Document

Relics"

·

At the time

it is done, exact copying can seem easy because it isn't necessary to

understand the underlying requirements and conceptual models embodied in the

solution being copied

·

But when

the copied implementation needs to change, as it inevitably does, this lack of

understanding of "what's really going on" makes it harder to know how

to revise and improve it

·

So

sometimes processes and information models persist even though they are no

longer serving much purpose

The Flavor Principle Cookbook (aka "Ethnic Cooking")

· The "flavor principle cookbook" by

Elisabeth Rozin, who analyzed 30 cultures and

sub-cultures to determine what patterns of flavors and spices characterize

different cuisines, presents "recipes" at an abstract level to guide

experimentation and culinary innovation

· e.g.

o

Oriental cooking

dominated by soy sauce (China, Japan, Korea, Indonesia) and fish sauce

(Vietnam, Laos, Thailand, Burma)

o

Indonesia: soy sauce,

brown sugar, peanut, chile

o

Provence: olive oil,

thyme, rosemary, marjoram, sage, tomato

o

Northeast Africa:

garlic, cumin, mint

Adopting Patterns

·

"If a

pattern fits, use it" sounds like reasonable advice But

how do we assess the "fit" of a pattern?

·

Is it

easier to adopt a pattern if there is no "As-Is" model?

·

How does

the abstractness of the pattern affect its applicability and fit?

Model from Scratch, or Adapt a Pattern?

The Process of Pattern Selection

·

Choosing a pattern is an iterative process

·

Whenever there is "business" going on

almost by definition that means there are buyers and sellers, or producers and

consumers. So we can apply that pattern to almost every situation to gain

insights.

·

Who has the power, the buyer or seller?

·

Who can set standards or terms/conditions in the

relationships? (who can choose the pattern?)

·

Who is the authoritative source of the information

involved?

·

What kinds of products or goods are being

"sold"

Applying Patterns to Achieve Insight

·

Sometimes we can get new insights about a business

problem or inefficiency by trying to apply a pattern to a context substantially

different from its usual one

·

We aren't likely to find a pattern that can serve

as a To-Be model, because we might have to make analogical or even metaphorical

assignments of activities and roles

· This is a brainstorming

or "thinking outside the box" technique

Different Ways to Frame the Application of Patterns

·

SELECT A

PATTERN "here are some observations about the university - classes and

majors are oversubscribed, some classes are underenrolled...

how could you eliminate or reduce these problems?"

·

INSTANTIATE

A PATTERN "how is the university like a supply chain and

marketplace?"

·

EVALUATE AN

INSTANTIATED PATTERN "can the university be viewed as a marketplace

operator that indirectly distributes degrees manufactured by a school or

department?"

Adapting to Patterns

·

If a

pattern almost fits, you can change the pattern slightly so it fits your specific

requirements or you can change your requirements so that the pattern fits

exactly

·

How do you

decide?

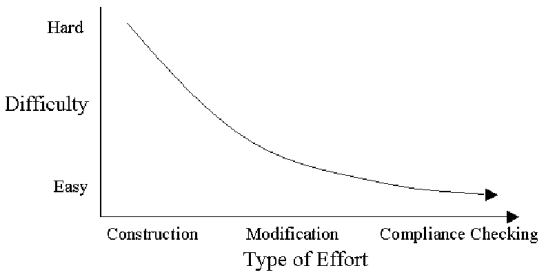

The Cost of Adaptation

·

"Differentiation

that does not drive customer preference is a liability"

·

What are

the costs for employees if a pattern is adapted?

·

What are

the costs for customers if a pattern is adapted?

·

How do

these costs change over the life cycle of the product/service/process?

Adapting a Pattern

·

A pattern

might be specified in terms of roles or elements that can be instantiated in

different ways

·

When does

an adaptation become a pattern in its own right?

·

We might

adapt a recipe by applying a different set of flavor principles to an old one

· We would be inventing a new recipe if we were

to come up with a new combination of spices to create a new flavor principle

Using Patterns

to Suggest Information Components and Documents

Every process

model needs information components that link threads of related document

instances within the process.

Key

Information Components:

o

Identifiers

for the transactions or the documents within them.

§ e.g. Purchase Order Number, Order

Reference, and Invoice Numbers, or application-based, like time stamps or

message identifiers.

o

Identifiers

for the participants in the process.

§ e.g. Social Security numbers, employee

IDs, business registration numbers, or other unique or contextually unique

values.

o

Identifiers

for the product or service that are mentioned in the transaction so that

authoritative information about them can be retrieved from any process that

involves it (pricing, ordering, invoicing, shipping, etc.).

o

Integration

or interoperability information, such as values or codes used by processing

applications or ERP systems.